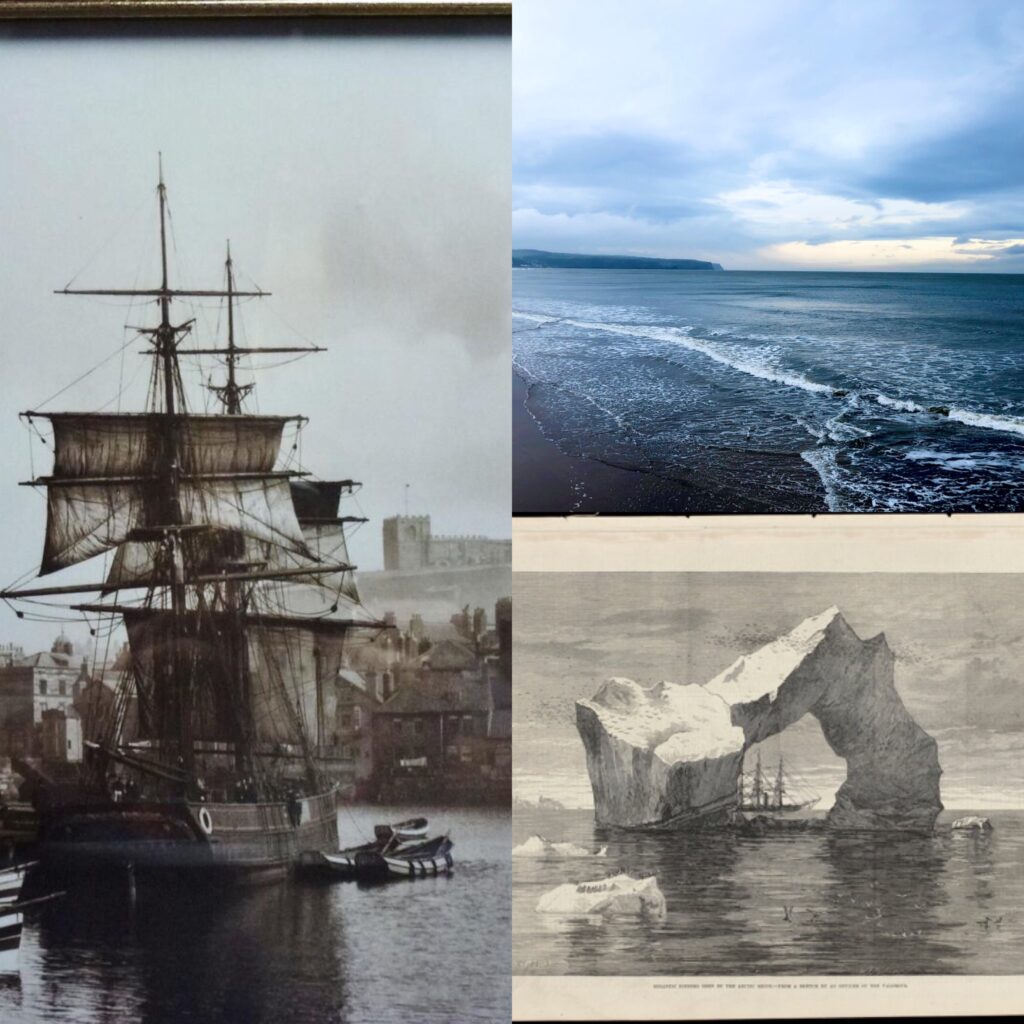

This story, which won the Young Walter Scott Prize 2019, was inspired by folk songs from the north-east of England – about the sea, Arctic whaling, and the press-gang. These set me reading nineteenth-century collections of songs, stories and poems in the dialect of Whitby and the North Riding. I was captivated by suggestive and onomatopoeic but now forgotten words and turns of phrase. The words had mostly Norse roots, and I realised that the dialect, like the weather and livelihoods of the people of this coast, had drifted to Whitby by sea from the far north.

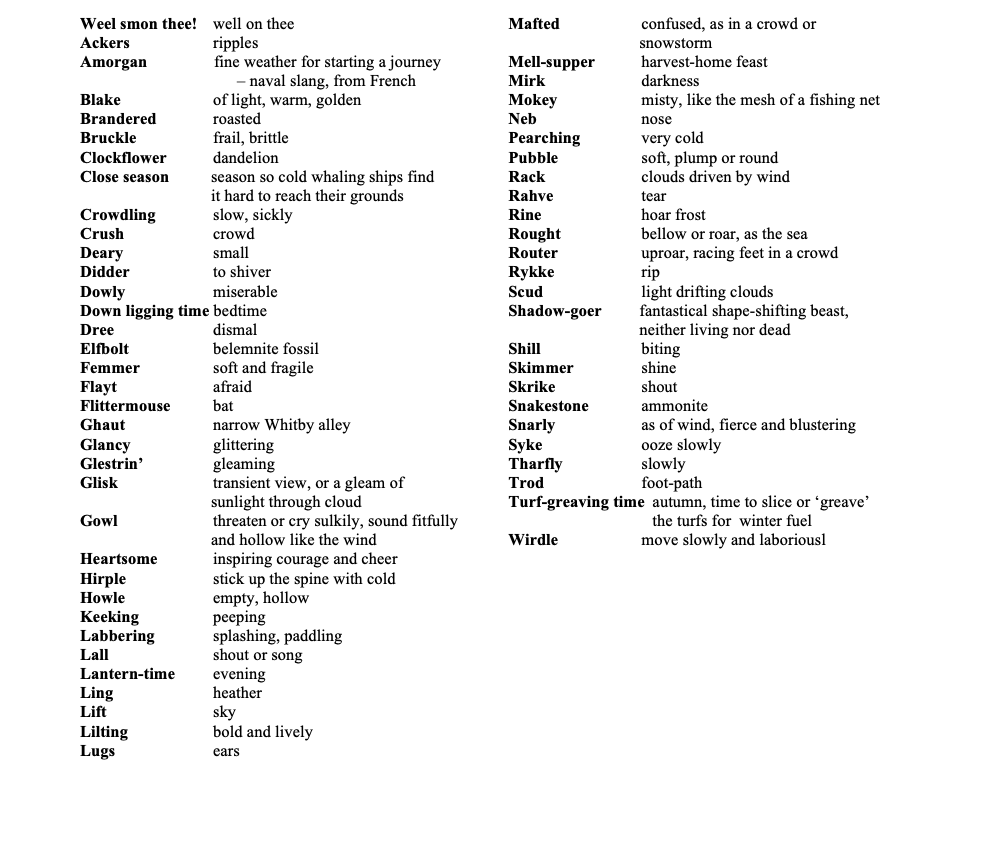

I drew on several nineteenth and early twentieth-century studies of the dialect of the area in my attempt to capture my main character’s voice. It is obviously not a perfect transcription of how she might really have talked. Even if I had complete knowledge of the dialect and how to transcribe it, writing like that would make it very inaccessible. Authors like Emily Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell who wrote in what they thought of as authentic dialect met with complaints from baffled readers. I compromised in favour of readability. I include a glossary at the end of the old Whitby words used, many of which I have only found in nineteenth-century studies.

The whalers set sail for Greenland in March and returned at the end of the summer. I was fascinated by the inversion of the usual pattern of feeling and association that this suggested; spring would have been a time of parting and sadness, autumn of hope and revival.

2nd October, 1793

I’m dreamin’ – a soundless dream o’ fallin’ ice.

A breath o’ wind comes – a sweet waft that mun ha’ come rustlin’ through meadowsweet an’ butter-cresses. Summat soft an’ warm reaches through t’snow an’ melts t’cold.

A deary little hand, like a pubble shell, scrabblin’ for my face – littler clingin’ fingers. I always know when she’s awake – t’ way Jamie says he knows in his sleep if his ship has shifted course.

She’s curled up, warm and sweet as a brandered chestnut in my cold bed.

“Let’s go, my honey bairn!”

Down t’ ghaut into t’ lighter dark. My tread allays so loud on t’cobbles. The stark pillars o’ t’ empty marketplace, an’ past Henrietta Street. This wakin’ world is chiller nor dreams o’ t’north, and t’ shill wind that gowls through t’streets is little like my bairn’s sweet summer breath, still warmin’ my neck while the rest o’ me is set a-didder.

Steps up into t’ black.

“One, two, three, four, five…there, honey bairn…” Town gone now.

Her little heart beatin’ again’ mine. Answerin’.

As my legs tire, them snarly gusts gain strength – t’ edge o’ winter in ’em.

“There thee be, church, hirplin’ under t’ wind as be thy way!” Them graves is sharp against t’ sky – it’s growin’ paler.

“An’ one hundred an’ ninety nine – top!”

Me feet find trod. I can hear the roughtin’ o’ t’sea in t’ mirk below.

“Here’s our nest i’ the hussocks, my bonnie! Mind yon morn when we found a mammy roe and her fawn, warmin’ it for us? That were a lucky sight! An’ how they twinkled away through t’ mokey dawn…”

I lap us snug and set to watch.

The lift brightens like t’ apples on t’wall at home, scud touched wi’ t’ same whisper pink that kisses babby’s bonny neb and lugs.

“There goes t’last flittermouse! Down liggin’ time for ’im. There be t’sun, keekin’ frae his black den. Risin’ aloft. Sitha how t’sea shivers and skimmers, silver like a glestrin herrin’!”

Now t’rosy glow catches o’ the rahvin’ manes o’ t’ billows – and on t’ sails o’ a ship comin’ home.

That’s my heart, swellin’ like a wave and crashin’ into my mouth. I know t’ build o’ the Stranger.

My bairn will meet her father today.

He’s pacin’ yon bruckle deck, lookin’ to t’ land, tryin’ to see his bairn’s face in his mind.

Or he’s lyin’ beneath t’ dim weight o’ t’ seas, or on some driftin’ sheet o’ clouded ice, t’ snow-blossoms siftin’ softly o’er him.

The Stranger takes t’ same course home as that she set. A clear mornin’ – armogan, Jamie said. T’ cold were givin’, the rine brushed from t’ fields like sleep-sand, an’ only t’ bones o’ snow left on t’ tops. I were so big wi’ babby I could hardly climb t’ stairs.

They all said I knew tears I were buyin’ when I wed him.

When t’ sun and t’ shoots is climbin’, when the rack runs afore t’wind like a swellin’ sail and t’ bare twigs stretch out to grab t’spinnin’ snatches o’ blue between –

then t’ men mun go. When all hearts should be singin’ wi’ the blackbird, there’s nobbut dree looks and dowly faces.

Most whalers scarce ken how a primrose looks, let alone a rose. But my Jamie do. ’Twere summer when we was courtin’, yon close season. Lanes white wi’ drifts o’ may, an’ him crackin’ on. O’ skeleton wrecks, o’ icebergs shaped like shadow-goers in a dream, o’ fathomless seas, marbled wi’ ice floes like t’cover o’ t’ Bible in St Mary’s – o’ ships cracked to shivers like nutshells under a wagon-wheel. He told how he were saved for me, by God’s will, when the Hope were crushed in t’ Davis Strait, another summer day when t’ ling blew purple above Whitby town.

Me standin’ under t’ fallin’ blossom wi’ dusk comin’ on, thinkin’ mesel’ on a frosted deck listenin’ to t’ hush while t’ ice snuck nearer. I weren’t flayt then – to fear t’north seemed foolish as fearin’ dreams. Besides, Jamie smiled at me so broad when’d done his tale that it drove t’ cold away. Not a lass this side o’ Middlesborough but were won by his lightsome smile, his heartsome tongue an’ his liltin’ free ways.

Dog roses nodded their compliments o’er t’ churchyard wall when we was wed.

Sweet and short were t’ winter, and t’ first snowdrop ended all. I said it worn’t right for him to go, crossin’ grey seas to lie in t’ stiff arms o’ distant lands o’ ice – not wi’ new life inside me, and stirrin’ in t’earth – his bairn and spring set to be born together. I said ’twas pride, this wish to tame t’ waves and bend t’ winds on sails, daring death. He said ’twas wantin’ pay enow’ to keep babby and me.

So I watched t’ Stranger sail, strainin’ my een to catch a glisk o’ t’gallants long after she’d dipped behind t’ sea. When again hedges grew heavy wi’ dog-roses, I told my bairn about her father and waited for backend. She bonnier by t’ hour – and he missin’ bright times niver to come again. Missin’ yon first laugh on t’sands while t’ wind chased sunny ackers o’er t’ Esk. Mell-supper at last, and we came home from long wanin’ days on t’ moors wi’ hands black wi’ blaeberries.

I longed for t’ flowers to be a-dyin’. How my heart did quiver and hop wi’ t’ first yellow leaf on t’ birk! T’ swallows makin’ ready for journeyin’, gatherin’ on t’ shrouds o’ t’ few ships left in harbour, flyin’ dark against t’ sunset to their song o’ lost summers – that tune as allus makes me think mesel’ a bairn again, seekin’ elfbolts and snakestones on t’shore, labberin’ in t’ foam.

While t’ skies grow wan and t’ woods weary, the hedges sear as t’ sinkin’ sun saps out t’ green – then all Whitby stirs wi’ hope.

The last weeks were wor nor ever. Watchin’ and seein’ naught but yon dree sea, t’ tide wirdlin’ in and wirdlin’ out – sometimes a sail that was not his, to make me sorrowful e’en when the rest o’ the womenfolk were singing for joy – and every day I did not see the Stranger, the fear growing’ that I never should. So many langsome tide-turns o’ empty water rollin’ on between my bairn and her father.

And yet she ever blithe and bonnie as t’ summer, growin’ and thrivin’ wi’ t’ other saplings o’ t’ year like all were reet enow.

“There’s naught ails thee, is there pet? Weel smon thee!” She’s grippin’ one o’ my fingers – her pubble little fist pearchin’. I croodle it in my breast.

Them sails, skimmerin’ under t’dawn, mun be a dream. I know I shouldn’t hope, but I can’t help it. Jamie were always more venturesome nor any wife could wish; but mindin’ t’ bairn, he mun have taken care o’ hissel?

He lives – I know it – I can feel it. Under them glancy sails his heart beats in time wi’ mine and babby’s.

I’m so sure I’ll even spare a thought for t’ other men – Nancy’s sweetheart, and little Davy – and t’ first mate as were so kind when we was courtin’.

The Stranger drags t’ moments behind her, tharfly as t’ white line o’ wake. How desperate slow ships do move. How has a crowdlin’ creepin’ shell like yon braved waves that lick high as t’ masts, and ice that closes round timber like t’fingers o’ death?

“Soon thou’lt see thy daddy. We’ll be there to meet ’im.”

She’s coming up-river now, but there’s this shadow fright on me that if I stop watchin’, when I turn back there’ll be naught but grey water. We’ll stay up here till t’ last, and then run – down an’ down…!

Time sykes by. I’ll think how his face will look when I put my bonnie into his arms, and that will pass it well enow.

“Now, my connie – ar’t ready? Let’s fly!”

The church-garth a blur, fast as t’blake sau’t wind – red stalks o’ briar snatch, but I rykke free – down, down, town spun out anunder, t’ roof-tiles hot to my een as stirred embers, glowin’ leaves.

The streets is full – eager faces in t’ gentle sunlight. I don’t know yon lass, but I smile anyhow… there’s Annie, and Esther whose youngest went off to sea for t’ first time in t’ Stranger. They all stand out o’ t’way for me. Times like this, Whitby is courteous as gentlefolks’ watering-places.

Down to t’ sands where t’ boats is pullin’ ashore.

And there he be. Smilin’, dark een bright as ever. A few flyin’ footsteps distant. Naught but clear mornin’ air betwixt us.

It’s no dream.

I put out one arm to steady t’ world. Too many folk around us, a router on t’ spinnin’ sands. Somehow I’m being pushed back, mafted wi’ t’crush. I hold babby out to him – high o’er t’ heads – and she’s dancin’ in his arms.

There’s a right go-to behind – t’ lasses look frightened. It doesn’t matter. Naught matters now.

He lifts her high into t’ sun, and she looks back at him wi’ a funny, muddled little face, een wide.

Strange hands snatch her from him.

The throng closes and I can’t see her – but I can hear her cryin’. My own voice skrikin’ –

“No! No!”

I see her arm, her head, her foot through t’ crush – and I have her! – deary, warm, femmer love. I gasp in her meadow breath like I were half drowned.

Only now I make t’ words out from t’ roar. All too sharp now, bruisin’ t’ air.

“The press gang!”

These bodies is a wall o’ ice and I’m clawin’, fingernails tearin’ through t’ cold.

Now I can see Jamie – een black holes, mouth set in a line, arms twisted behind him. ‘I’ll come back – forgive me! Don’t let t’ little one grow too fast!’

His face burns itsel’ onto my brain and his een swallow me. Black. Deep as seas, sucking me down into t’chill.

None but childer in t’ streets this lantern-time. I’m worn wi’ greetin’, a pool at low tide left howle by t’ sea.

From one o’ t’ darker ghauts, I hear sobs – “The war will be long – I know it – they a’ say so! And he may be killed afore tis o’er.”

I don’t heed t’ mother’s words o’ comfort.

I don’t care what length it takes to reach t’ cliff top now.

Jamie will niver know my bonnie seven month pet. Next year she’ll be another bairn – and he won’t be back next year, nor next. There’ll be no peace. Back in t’ winter, t’ French killed their King. I didn’t mind it then, for Jamie were home and my belly swellin’.

Her eyes is deep blue, gleamin’ like wet pebbles under t’ wave.

She’s smilin’ – t’ way that only bairns can smile, fair like a lall o’ joy. I mun smile back, whether or no. She gurgles and squirms on t’ grass between t’ graves, crawls to where one o’ t’last clockflowers is shinin’ and picks it, crushin’ it in her little fist. She’s not learned to pick flowers without spoilin’ – but clockflowers grow strong.

“There’s nowhere thy daddy won’t see now, honey bairn. India, an t’ Cape, and t’ coast o’ Barbary… Africa where there’s no backend nor winter, only one long summer all year round. We’ll wait here – we’ll work, and we’ll live – on this cliff – in t’ churchgarth, in town, in fields, on t’ moor… an’ one day t’winds’ll blow him back to us. Happen he’ll cast up here wi’ an epaulet on his shoulder gold as them clockflowers, an’ enow prize money so he niver has to flit again. He’ll bring thee a parrot that talks from t’ isles in t’ west, and the sharpest spices from out o’ t’ east. Don’t grow too fast.”

Glossary

1 Comment

love it!!!!